. . |

Date of Birth | 1866-00-00 | |||

| Place of Birth | Horodyszcze (Ukraina) | ||||

| Date of Death | 1930-02-08 | ||||

| Place of Death | Warszawa | ||||

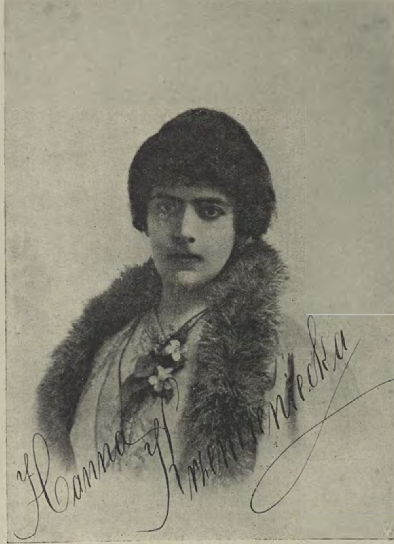

| Pseudonym and cryptonym | H. Krzemieniecka; Hanna Krzemieniecka | ||||

| VIAF ID | 166400239 | ||||

| Public Domain. In: Tygodnik Ilustrowany (Warszawa), 1930, nr 9, s.173. |

|||||

Hanna Krzemieniecka’s original first name was Janina, descending from the Bobiński family in Żyrkiewiczowa. She was born in 1866 in Horodyszcze, Ukraine, and died in 1930 in Warsaw. She was a writer, theologist, socio-cultural and national activist, and translator. She descended from a noble family, and was the daughter of Sylwan Bobiński of the Leliwa coat of arms and Pelagia Socharzewska. Her father was a doctor and patriot, who took part in destroying a list of participants of the Szymon Konarski conspiracy; in the presence of military policemen. He committed this act during his study at the Medical and Surgical University in Vilnius in 1838. As a result of this act, he was subjected to torture and subsequently jailed. After regaining his freedom in November of 1841, he graduated with a medical degree from Kazański University, despite some difficulties along the way. Krzemienicka was raised, along with her many siblings, in a patriotic and cultural atmosphere. She was homeschooled. Her life and works fall on a stormy period in Polish history, lasting through both World Wars and the interwar period.Krzemieniecka, already a teenager, showed her interest in writing and began her literary involvement at an early age. In 1886, she married Walery Furs-Żyrkiewicz, who was Polish despite occupying a position as a general of the Russian armies. Their marriage yielded four children, including their daughter Ewelina Pepłowska (1887-1969). Ewelina followed in the footsteps of her parents by actively participating in national movements. For example, she was an activist in Narodowa Organizacja Kobiet (National Womens’ Organization) from 1930 to 1935, and a member of Stronnictwo Narodowe (Polish National Party). Koło Delegatów (Circle of Delegates) meetings were also carried out in her apartment and in Walery’s.

In 1900, Krzemieniecka moved to Warsaw, thinking of the good of her children and wanting them to grow up in a Polish environment. At this time, she debuted with her short story Przed wyrokiem (Before The Verdict, 1901). Shortly after this, her husband moved to Warsaw after resigning from his position as commanding officer of the fortress in Władywostok at the beginning of the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905). After the death of her husband in 1906, who died of Meningitis, Krzemienicka focused even more on her literary and social work. During the protest against the russification of schooling, she organized secret meetings, readings and lectures in her own apartment. She also led public lectures in the organization Stowarzyszenie Równouprawnienia Kobiet (Women’s Rights Society), raising topics related to the materialistic doctrines’ crisis, among others. Her opposition towards material goods developed as a result of her interest in theology and Indian philosophy. Krzemieniecka translated the book Główne zarysy teozofii (Main Outlines of Theology), published in 1911 by Théophile Pascal (1860–1909). Pascal was a doctor and general secretary of the French Sect of the Theosophical Society. In 1910, Krzemieniecka published the novel A gdy odejdzie w przepaść wieczną… Romans zagrobowy (And When You Depart into An Eternal Abyss… A Romance Beyond The Grave), which promotes theosophical ideas through a fictional story. The detailed illustrations in this book were created by Kazimierz Stabrowski, who was the founder of the Theosophical Society in Warsaw.

During World War I, Krzemieniecka actively participated in aiding victims of the war, becoming a member of Zarząd Towarzystwa Pomocy Ofiarom Wojny (Board of Aid for Victims of War Association) and actively operating in Liga Polskich Kobiet (League of Polish Women). After the end of the war, she began working with the monthly magazine Walka z Bolszewizmem but continued writing short stories, novels and philosophical essays. Within her works, among others, one can find the story Lecą wichry (The Gales are Flying, 1923), for which she received an award in the Jubilee Contest Kurier Warszawski.

Krzemieniecka’s works were well known and commonly read at the turn of the 19th and 20th century. However, her works are more or less forgotten in today’s age. She mainly wrote novels and accounts, which presented social and psychological topics. Her works concentrated on analyzing interpersonal relationships, characters’ internal conflicts, and social and moral problems. Her literary works are characterized by a deep interest in the psychology of her characters and social and philosophical issues.

In the longest, and equally most significant, of her creative works entitled Fatum. Studium psychologiczne (Fate. A Psychological Study, 1928), Krzemieniecka presents problems and dilemmas similar to those which she experienced in her own life. The work is written as a customs story with moralizing elements, which allowed her to convey main theological concepts and, in particular, her own idea of truth. The events in the book take place in a charming manor in the center of Kyiv, which the widow Salomea rents out to a few pensionaries. Krzemieniecka took great care in creating small genre scenes, but critics thought that they required a specific sense of humor to understand. Although the characters and situations were inspired by earlier motifs such as delusional hopes, deception, the pursuit of a carefree lifestyle; she specifically chose them in order to show the superficiality and the mundaneness of everyday life. She created the character Iza, a female protagonist who she attempted to free from stereotypes in order to discover her true nature. This truth turned out to be frightening, showing that Iza was deep down fascinated with suffering and sacrifices. However, the protagonist realizes that she is a priest collecting donations on the altar of the holy spirit, but her immortal “I” is aware and longs to get closer to “The Absolute”, regardless of the consequences. This story is an interpretation of the theological doctrine viewed by Krzemieniecka, who thought that truth is God, and that God is present in everything; never-ending and eternal. She strongly desired to convey that the idea of “truth” can seem contradictory and even ugly, because human understanding is restricted in many ways. Despite the varying interpretations, the book made a profound impact on readers, attracting not only spiritism aficionados, but average readers as well.

Hanna Krzemieniecka’s writing style, which promoted patriotism and dedication, was regarded by critics as valuable in the educational context of her works. In terms of her present popularity, there was an attempt to name a long street in Warsaw after her, however this attempt was not realized. Instead, Zygmunta Krasińskiego street was elongated to Księcia Janusza street according to the city’s plan from 1935. Krzemieniecka was buried in Powązkowski cemetery in Warsaw.

Her works, although rarely mentioned in the context of Polish literature at the turn of the 19th and 20th century, stand as an interesting example of psychological and philosophical literature in this period. Her involvement in national movements and theological interests also emphasize her versatility and intellectual depth.

WORKS

A gdy odejdzie w przepaść wieczną...: romans zagrobowy, Warszawa, s.n., 1910.

A gdy odejdzie w przepaść wieczną, [B.w], Imprint sp. z o.o., 2010.

Cześć silnym jednostkom… [Inc.], [In:] Z dni jubileuszowych Pauliny Kuczalskiej-Reinschmit d. 6 i 7 maja 1911 r., Warszawa, [s.n.], 1911, s. 11-12.

Fatum : studyum psychologiczne, Warszawa, J. Fiszer, 1928.

Lecą wichry! = powieść, Poznań, Warszawa, Wilno, Księgarnia św. Wojciecha, [1923]. [Powieść, nagrodzona na konkursie jubileuszowym „Kurjera Warszawskiego”].

Mężczyzna oskrzydla kobietę...[Inc.], Chochoł, Warszawa, Wydawnictwo „Społeczeństwa”, 1909, s. 26.

Ofiary, [In:] Jednodniówka poświęcona cieniom Marji Konopnickiej, Lublin, [s.n.], 1911, s. 92-94.

Pod cichą falą: szkice i obrazki, il. K. Górski, Warszawa, skł. gł. Gebethner i Wolff 1902. (Zawiera: Przed wyrokiem; Szczęście rodzinne; Troska przekwitłej elegantki).

Przed wyrokiem. Chwila z życia kobiety, „Prawda”, 1891, nr 46, s. 542-545; nr 47, s. 554-557; nr 48, s. 566-569.

Wrażenia balowe. Igraszka psychologiczna, „Warszawski Dziennik Narodowy”, 1936, nr 219B, s. 4.; nr 220B, s. 4; nr 221B, s. 4; nr 222B, s. 4; nr 223B, s. 4; nr 225B, s. 4; nr 226B, s. 4; nr 227B, s. 4; nr 230B, s. 4; nr 232B, s. 4.

Żywe uosobienie idei: pamięci T. Prażmowskiej-Wołowskiej, "Bluszcz", 1912, nr 25, s. 288.

Literal translation

Chatterji J. C., Filozofia ezoteryczna Indyi : wedle Vedanty (Uttara Mimâmsa) , przekł. z fr. Hanny Krzemienieckiej, Warszawa, [s.n.], 1911.

Pascal T.,Główne zarysy teozofii, przekł. H. Krzemienieckiej, Warszawa, [s.n.], 1911.

Walka Międzynarodówki bolszewickiej z religją , przeł. z fr. H. Krzemieniecka, Warszawa, Zjednoczenie Polskich Stowarzyszeń Rzeczypospolitej, 1927.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

I. M., Śp. Janina Żyrkiewiczowa, „Kurjer Warszawski”, nr 42, s. 4. (wydanie poranne).

Krzemieniecka Hanna (1866 – 1930), [In:] Bibliografia literatury polskiej Nowy Korbut T. 14, Literatura Pozytywizmu i Młodej Polski: Hasła osobowe: G - Ł, Warszawa: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, 1973, s. 550-551.

Krzemieniecka Hanna, [In:] Lechicki C., Przewodnik po beletrystyce, Poznań, Naczelny Instytut Akcji Katolickiej, 1935, s. 268.

L. R., Z wiedzy, literatury i sztuki, Ś. P. Hanna Krzemieniecka, „Rodzina Polska”,1930, nr 5, s. 149.

Lascaro [Pajzderska Helena], Romans zagrobowy, „Literatura i Sztuka. Dodatek do Dziennika Poznańskiego”, nr 46, Poznań 1911, s. 730-732.

Lubierzyński F., Polska powieść teozoficzna, Bluszcz, 1914, nr 17, s. 177 ; nr 18, s. 191-192. oraz „Głos Narodu”, 1914, nr 98, s. 2; nr 99, s. 2.

Mazur A., "Czytano je z zajęciem, a często ze wzruszeniem" : o zapomnianych powieściach Hanny Krzemienieckiej, "Wiek XIX", R. 12 (2019), s.107-129.

Moszczeńska I., Ś.p. Janina z Bobińskich Żyrkiewiczowa „Hanna Krzemieniecka”, „Tygodnik Ilustrowany”, 1930, nr 9, s. 173.

Mysiakowska-Muszyńska J., Kobiety niepokorne, czyli o liderkach Narodowej Organizacji Kobiet. Szkic do portretu zbiorowego działaczek Narodowej Demokracji (1919–1929), „Polish Biographical Studies”, 2017, Nr 5, s. 13. DOI: 10.15804/pbs.2017.01

Pamięci zasłużonej Polki, „7 Dni”, 1930, nr 13, s. 11.

Piwiński L., Hanna Krzemieniecka: Lecą wichry! - [recenzja], „Przegląd Warszawski”, 1923, T. 3, nr 22, s. 98.

Przewóska M. Cz., Ś.p. Janina Żyrkiewiczowa (Hanna Krzemieniecka), „Gazeta Warszawska”, 1930, nr 46A, s. 4.

Sierotwiński S., Krzemieniecka Hanna (1866-1930), [In:] Polski słownik biograficzny, T. 15, Kraków, Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich,1970, s. 515-516.

Słownik pseudonimów pisarzy polskich XV w. - 1970 r. T. 4, A-Ż : nazwiska, ed. E. Jankowski, Wrocław, Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, 1996, s. 820.

Smolarski M., Hanna Krzemieniecka : dzieje myśli i twórczości, Warszawa, skł. gł. Kasa im. Mianowskiego, Instytut Popierania Nauki, 1935.

Ś.p. Janina Żyrkiewiczowa (Hanna Krzemieniecka), „Bluszcz”, 1930, nr 10, s. 12.

Teresińska I., Krzemieniecka Hanna 1866-1930, [In:] Dawni pisarze polscy: od początków piśmiennictwa do Młodej Polski: przewodnik biograficzny i bibliograficzny, T. 2, I – Me, ed. R. Loth, Warszawa, Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne, 2001, s. 289-290.

Walaszczyk I., Scenariusze inicjacyjne w "Fatum: studium psychologicznym" Hanny Krzemienieckiej = Initiation scenarios in Hanna Krzemieniecka "Fatum: a psychological study", "Przegląd Humanistyczny", 2023, nr 2, s. 121-135. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31338/2657-599X.ph.2023-2.9

Walewska C., Nad świeżą mogiłą Janiny z Bobińskich Żyrkiewiczowej (Hanny Krzemienieckiej), "Kobieta Współczesna", 1930, nr 11, s.18-19.

Z., Hanna Krzemieniecka, „Kurjer Warszawski”, 1934, nr 356, s. 13. (wydanie wieczorne).

Z. W. [Wasilewski Zygmunt],Wspomnienie o Hannie Krzemienieckiej. "Myśl Narodowa", 1932, R.12, nr 9, s.125-126.

Zawiszewska A., Między Młodą Polską, Skamandrem i Awangardą : kobiety piszące wiersze w dwudziestoleciu międzywojennym, Szczecin, Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Szczecińskiego, 2014.

Żyrkiewicz L., Patriotyczne tradycje domu gen. Walerego Żyrkiewicza, „Stolica”, 1963 nr 37, s. 14.

Author biography: Wiktoria Świętuchowska

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC Attribution - NonCommercial 4.0 license. License text